|

Imagine your foot was redesigned to add inches of thick padding under your heel bone that enabled you to walk silently whenever you wanted. Kind of like a super power. You and your similarly equipped friends could go about your way without making a sound. Then add to that the ability to communicate at very low frequencies without opening your mouth. Say that these sounds could travel for miles and be heard by others like you. Like a whale, your messages could cover vast distances at the speed of sound. What if your senses were so well developed that you could smell water more than a mile away and sense thunder at great distances from vibrations in the soil? And what if those senses were in an appendage that contained tens of thousands of muscles and not a single bone. An appendage with the strength to lift 700 pounds and so flexible that it was capable of lifting a single blade of grass? You would be remarkable. You would be part a “memory” (or herd) of bright, caring, communicative and powerful individuals. You would be a perfect tree eating machine. A gardener, of sorts, for the African wild. Our travels through Africa showed us much of the handiwork of these gardeners. Mostly, swaths of small trees and bushes pushed over, pulled up and partially eaten. Then one afternoon we got to watch the process with a small memory of elephants on the Maasai Mara savanna. In the image above you can see the youngest one is still nursing and not participating in the green feast. The rest are consuming a tree they have just pushed over. Then, just above, a younger one is chewing on a branch. And then below, pushing on the partially decimated tree to get at a chosen morsel. The trunk, obviously, is essential to eating a tree and to much of everything else the elephant does. It is used to gather water, express affection and to give a young one a needed nudge. But consider what a challenge it must be to learn to use a trunk. Elephant babies are born with a short recessed trunk that grows to full extension in just a few days. With thousands of muscles and no bone, it cannot be easy to learn to control this all important appendage. The images below show just three skills necessary to live with a trunk. First, you have to learn to avoid stepping on it. Then, to lift it and hold something. Learning to twist it is essential to many tasks like grasping a twig.. But, in the early learning stages sometimes a full body twist to get the trunk just right. Success, however, can be it's own reward as this youngster brings a twig to its mouth. But sometimes, the stress of learning to use a trunk becomes too much. And, just when you need it most, your sibling can help you give it a rest. _ _ _ _ _

All photos and text are copyright Clinton Richardson. The images are from the author's Safari Collection at Trekpic.com. If you like these posts, please tell your friends about the Venture Moola blog at Readjanus.com. Want to plan your own safari? If so, feel free to check out the outfitter we used at Porini.com. And, feel free to share this blog. The more readers the better. Click here if you would like to get a weekly email that notifies you when we release new entries. Or, click in the side column to follow us on Facebook or Twitter. This week our posting is rated Feline X as we recount our first stop on an afternoon drive out of Lion Camp. After lunch and time to reconnect with friends from earlier camps, we headed out in an open Land Cruiser for our afternoon drive with a couple from California and a mother and daughter from Canada. Our driver took us directly to a spot where several lions, and a few safari vehicles, were stationed. The lions, one male and a few females, were near a zebra kill that the male claimed exclusive rights too. He was not eating when we arrived but he was fully engaged with keeping the females away from the kill. He might have been successful if he had been more single minded or if the females did not have their ways. Above, you can see him keeping a female away from the kill. She stayed at a respectful distance so long as he remained near. Not far away two females were completely ignoring him. Once he made his point to the encroaching female and she backed off, he ambled away past these two females to a nearby tree where three females were lounging in the shade. He had not forgotten the kill. He stopped to turn around and roar in the direction of the kill before he engaged with these three females. It was enough to keep the female who lingered near the kill away from her anticipated meal. But then it was time to procreate. The male chose a female and started nuzzling her and then mounted her. Another roar from him and one for her when they was done. Then, slowly and panting, he ambled back to his kill. No one else approached the zebra carcass. After standing next to the kill for a few minutes, he returned to the tree where the females were lounging and mounted another female. Again, when he was done both he and the female let out a roar and he left panting. This sequence repeated itself a few times until the tired male sat with the females and watched the original encroaching female lunch on the kill. The picture below shows the moment when feminine wiles trumped male's effort to monopolize the kill. The female now had the carcass to herself and chomped away at what remained of the zebra. Before long, though, she had company of another sort. A second female who approached but did not challenge for the zebra. Instead, she sat close by to wait for a turn. We drove on soon after this. We were less than an hour into our afternoon drive and had already seen a lot. Would we see anything as interesting during the rest of the day's drive? The answer turned out to be yes. Before the end of the day, we would learn how to eat a tree and witness a mother Cheetah and her three cubs as they searched for prey on the plain. More about that later. _ _ _ _ _

All photos and text are copyright Clinton Richardson. The images are from the author's Safari Collection at Trekpic.com. If you like these posts, please tell your friends about the Venture Moola blog at Readjanus.com. Want to plan your own safari? If so, feel free to check out the outfitter we used at Porini.com. And, feel free to share this blog. The more readers the better. Click here if you would like to get a weekly email that notifies you when we release new entries. Or, click in the side column to follow us on Facebook or Twitter. There was no game drive on our last morning at Rhino Camp. Instead, we and two other guests were headed to Lion Camp in the Maasai Mara by way of Land Cruiser and small plane. The rains had made the nearby grass airstrip unusable, so we had a 90-minute drive ahead of us to reach our plane’s new departure destination in Nanyuki. By 8:00 a.m. we were off in a fully loaded safari vehicle with our driver, spotter, camp director and one other. The morning air was crisp as we headed off. We quickly passed the airstrip we landed on just days earlier and continued driving on dirt roads for a full 40 minutes until we reached the gates of the conservancy. From there, we continued on a wider dirt road that eventually became paved. We began to see people on the roadside and the occasional one-story building. Most people were walking but as we drove on we saw some cars and motorcycles and goats. Most of the children were in school uniforms and most buildings had hand painted signs. As we got close to the city, the streets and buildings got more elaborate. Billboards appeared next to a four lane road we turned onto. One described a local bank as “the bank for interesting people.” We turned off the four-lane road before reaching Nanyuki to make our way to the airport. After finding a closed gate where we hoped to enter the airport, we doubled back for route two. This route took us through a gated animal club with a tree lined road that led to another gate through the club’s animal orphanage where we saw young cape buffalo, hippo, ostrich and other animals. When we reached the back gate of the club, we found ourselves on a dirt path that paralleled a black asphalt runway. Soon we were waiting on the tarmac near the plane. We said our goodbyes to our hosts and exchanged stories. While we were waiting for passengers from another outfitter, our driver made his way into the cockpit to check out the plane. Had he flown before? When we asked, he straightened his body and jumped straight in the air like the Maasai warrior he was. “Only like this,” he said. Of course the jump looked different on the tarmac with our driver in a leather jacket and jeans standing in front of an airplane. The traditional Maassai culture that is rooted in village life and dependence on cattle is still very much alive in Kenya. The Maasai we met in the camps and as we traveled are caught between two worlds and many are working thoughtfully to adjust. Never was this more apparent than when a Canadian guest posed a simple question to the driver and spotter who picked us up from the airplane in the Maasai Mara to take us to the Lion Camp. "How many wives would you like to have?" She asked. Our driver and spotter both appeared to be in their late 20s or early 30s and both were dressed, as the gentlemen in the image above, in the traditional colorful attire of the Maasai. Each was married with one wife. Our spotter answered first. "If I work hard and can afford more, I would like to have three or four wives," he said. "They will tend my cattle and increase my wealth." Or driver agreed. He would like to have three wives. The number of children and wives you have define your prosperity in traditional Maasai society. But not all the Maasai we met agreed. Our driver on later game drives in the Maasai Mara was a prosperous man. He had taken the earnings from his guiding and invested in property. In addition to the cattle and livestock he owned, he also owned apartments that he rented out to others. "The world is changing," he said. "One wife is enough for me." Our flight from Rhino Camp to Lion Camp was a twelve-passenger single prop plane that made two stops as we flew across the Great Rift Valley. Each time we dropped off or picked up passengers. In less than 90 minutes we touched down on a large grassy field in the Maasai Mara region of south Kenya. There we met our hosts and boarded a Land Cruiser for the ride to Lion Camp. What would we see during our next four days? As the short ride into camp demonstrated, it would be plenty. We would not be in the vehicle long before we reached camp, less than 20 minutes, but before we were far from the landing strip we came upon two sets of elephants feeding their young along a meandering stream. One mother was alone with her calf. The other had company. If you look closely at either picture, you can see that the mother is still nursing. Shortly after this welcome we continued on and followed the road past a watering hole. There, equally disinterested in our progress, were the three cheetah shown above and below. We arrived in camp in time for lunch and then settled into our tent. As with every other camp, our hosts were gracious and attentive. And, like the other camps, the management and staff were all Maasai. This camp was set up beside a river that was home to a family of hippos. The guest tents were arranged to face out upon a vast plain of grass into the conservancy. Lions and elephants and other game would fill the nights with sound. We were at Lion Camp. The afternoon game drive would start at 4 o'clock. Postscript: I thought about including the names from Bill Watterson's great comic strip Calvin and Hobbes in the title because the young cheetah's pose above so reminded me of Hobbes in the comic strip. Maybe all cats sleep this way but the similarities came to mind immediately when we saw the cheetahs lounging outside Lion Camp. But since Hobbes is imaginary and a stuffed Tiger, I decided the allusion to Hobbes would be lost on most. _____

All photos and text are copyright Clinton Richardson. The images are from the author's Safari Collection at Trekpic.com. If you like these posts, please tell your friends about the Venture Moola blog at Readjanus.com. Want to plan your own safari? If so, feel free to check out the outfitter we used at Porini.com. And, feel free to share this blog. The more readers the better. Click here if you would like to get a weekly email that notifies you when we release new entries. Or, click in the side column to follow us on Facebook or Twitter. Time for a break from Africa to reflect on advancements in paleontology and the modern understanding about what's flying around in your backyard. It turns out that not all of the dinosaurs met their demise in the great extinction that ended the Cretaceous Period some 66 million years ago. Surprised? Consider checking out a new book by the University of Edinburgh's Steve Brusatte that provides a good summary of how modern science has revolutionized our understanding of dinosaurs, what caused their sudden extinction (after 200 million years of predominance on our planet), and how one group of dinosaurs survived to rule the earth's skies. Steve's book, The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs - A New History of a Lost World, is available at Amazon.com and elsewhere. Decades of dinosaur bone finds, advances in technology and the abilities of high-powered computing have rendered what I learned about dinosaurs in school obsolete. Serious students of the subject no longer understand dinosaurs to be the slow moving, cold blooded creatures we were taught had somehow unwittingly managed to dominate our planet for ages until they mysteriously disappeared. Today, we understood dinosaurs were warm blooded creatures of great diversity who managed to fill just about every ecological niche available on our planet's landmass. They survived long enough to witness the break up of the earth's giant continent Pangea into the multiple continents that make up today's globe. They dominated the planet for so long that it is hard to contemplate. And their demise 66 million years ago was not caused by some fundamental flaw in their makeup. Instead, it took a freakish cataclysmic event - the collision into the Yucatan Peninsula of a deep space object the size of Mt. Everest. This asteroid was traveling with such force and speed that it drove itself 25 miles below the earth's crust and into the earth's mantle. Known as the Chicxulub asteroid, this object likely hit at a speed one hundred times faster than a jet liner and released the force equivalent to "a billion nuclear bombs' worth of energy." Enough force to change the planet's landscape into a barren wasteland alive with volcanic activity. It's the stuff of disaster movies only it actually happened, Fortunately for us, our nascent ancestors were small creatures at the time, likely living underground or in niche circumstances that somehow enabled them to survive the ages of nuclear winter that followed. Another survivor, surprisingly to some, were the airborne cousins of the ferocious velociraptor, what we commonly call birds today. Of course, this was not always the accepted view. When we were kids, dinosaurs were fascinating but no one connected them to birds. But now, paleontologists can tie unique physiological features of birds to ancient dinosaurs. It turns out that some of the things that make birds capable of flight are the very features that enabled ancient sauropods and therapods (think the gigantic brachiosaurus and tyrannosaurous) to become so incredibly large. Steve Brusatte catalogs several genetic qualities that made it possible for these dinosaurs to become so large and for birds to fly. First and foremost is a unique system for breathing that is more efficient and lightens the weight of the creature's bones. Sauropods, therapods and birds can extract oxygen from the air both when they inhale and exhale making them highly efficient breathers. Air sacs in the bones of these creatures capture air as it is inhaled and when exhaled provides oxygen for absorption. It is more efficient that what we mammals have. It also makes bones lighter and easier for birds to dissipate heat. Could the ability to travel great distances quickly through the air and dissipate heat quickly be the advantages that enabled the dinosaur-birds to survive the cataclysm of 66 million years ago that killed off most of their relatives? Will these advantages keep them alive through the next mass extinction? And when that cataclysm comes, will we all wish we were birds? _ _ _ _ _

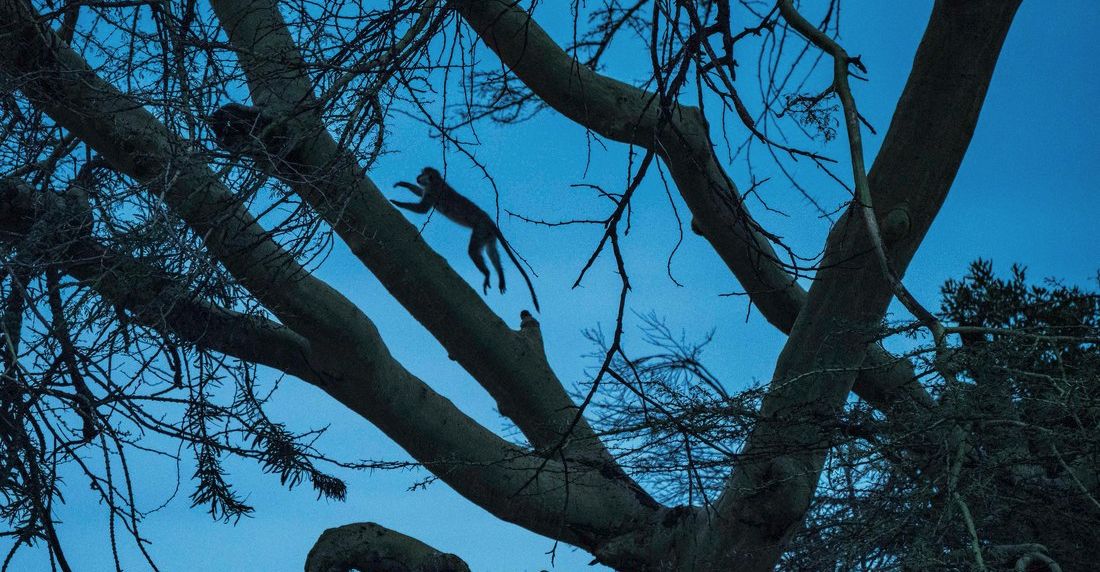

Next week back to our safari series with Safari 16: How Many Wives Would You Like to Have? All photos and text are copyright Clinton Richardson. The images are from the author's collection at Trekpic.com. If you like these posts, please tell your friends about the Venture Moola blog at Readjanus.com. And, feel free to share this blog. The more readers the better. Click here if you would like to get a weekly email that notifies you when we release new entries. Or, click in the side column to follow us on Facebook or Twitter. Reports of an extended drought in Kenya made me hesitant about scheduling our trip. You have to do it well in advance, almost 12 months, and at the time we made reservations parts of Kenya had been in drought for years. I could never tell, however, whether the areas we would be traveling to had suffered from the drought. I was not familiar enough with our destinations to match them to the online drought reports I was seeing. In the end, I deferred to the advice of our outfitter. Our leap of faith was rewarded with a wet spring and summer in Kenya and an abundance of game when we arrived. All during our trip, we were reminded of this rain by the tall grasses and the large number of young and pregnant animals. Among the zebra, it seemed like every third animal was heavy with child or being followed by one. We, of course, were traveling during the dry Fall season. Years of hearing about steaming jungles and hot equatorial regions had me anticipating heat and lots of it. As it turned out, preconceptions were wrong. The climate was much more temperate than I expected. We were not in sweltering jungles but, instead, cooler at high altitude in grasslands. Our equatorial African weather was what you would expect if you moved the wildlife to Denver for the summer. Cool mornings and evenings with moderate temperatures in the afternoon. I had been told this by a friend before we left but, still, it was a surprise. Our experience with clear skies, however, changed abruptly on our second day at Rhino Camp. Clouds gathered during our morning game drive and then, just before our scheduled afternoon drive, the skies dropped buckets of rain throughout the savanna. For the next few days, here and at the Lion Camp, rains would come each evening raising creek levels and making the roads wet and slick with mud. To our Maasai drivers and spotters this presented no problems. Drives went on as usual even when the roads got messy. On our last day at Rhino Camp, the rain and a heavy wind hit just as we were starting our afternoon drive. We all loaded ourselves quickly into the vehicle and began rolling down the canvas side protectors with their vinyl 'glass' windows. Our guides worked frantically to secure these panels from the outside until the passenger compartment was mostly dry. Our driver started the engine and began driving up the slick road. Wet cross winds whipped at the vehicle as we made slow progress. Visibility was low and our now spotter was struggling with front side panel. The rains were drenching the front compartment. No complaint from the spotter but the other guests and we elected to suspend the drive and return to camp. It was a good decision. Even though the skies cleared about 20 minutes later (which meant our sister vehicle was having a successful drive), we were treated to a cool afternoon around a campfire overlooking a busy waterhole. While we sat and exchanged stories, a small herd of grant's gazelles came and took their refreshment. And awhile later, a dozen or so baboons arrived and ran off the gazelles to have the space to themselves. Then a troop of vervet monkeys started moving between trees next to the waterhole. The one below was returning to a high spot to keep an eye on the baboons. When it got dark, we could not see what was happening across the stream that separated us from the waterhole. With an overcast sky far removed from city lights, it was very dark except for the flames from the fire and muted lights in the nearby dining tent. Just because we could not see the waterhole did not mean it was abandoned. Notwithstanding our conversation, we could hear movement and the occasional grunt across the stream. When a staff member arrived with a strong flashlight we were treated to this sight across the stream. Not bad for an afternoon off. Those in the other vehicle who continued in the rain returned with stories of great sightings but none of us felt deprived. The conversation around the fire and the chance to see rhino from ground level just across the stream made it another great evening. The next morning we would be up early to catch a bush plane to Porini Lion camp in the Maasai Mara region. The rains that had not interfered with our game viewing had washed out the grass runway next to the camp so our journey the next morning would take us by safari vehicle through the conservancy, across rural Kenya, through a wildlife club and to a private airstrip in Nanyuki. More about that next week. _ _ _ _ _

All photos and text are copyright Clinton Richardson. The images are from the author's Safari Collection at Trekpic.com. If you like these posts, please tell your friends about the Venture Moola blog at Readjanus.com. Want to plan your own safari? If so, feel free to check out the outfitter we used at Porini.com. And, feel free to share this blog. The more readers the better. Click here if you would like to get a weekly email that notifies you when we release new entries. Or, click in the side column to follow us on Facebook or Twitter. |

the blog

Travel, history, and business with original photos.

your hostClinton Richardson - author, photographer, business advisor, traveler. Categories

All

Archives

July 2023

Follow us on Facebook

|

Check out Ancient Selfies a 2017 International Book Awards Finalist in History and 2018 eLit Awards Gold Medal Winner and

Passports in his Underpants - A Planet Friendly Photo Safari a 2020 Readers' Favorite Winner in Nonfiction

Site Copyright 2024 by Clinton Richardson

RSS Feed

RSS Feed