|

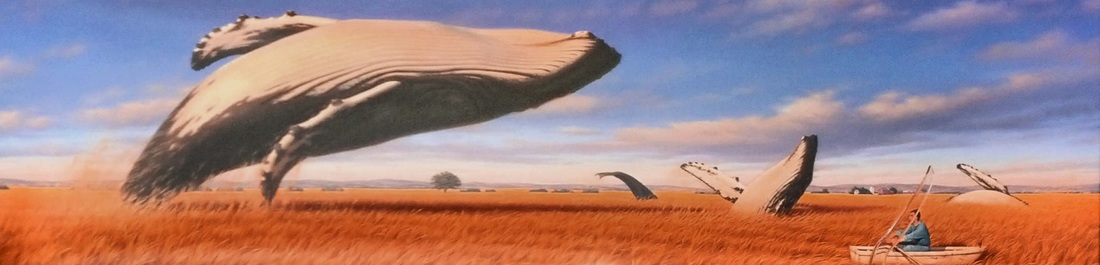

Occasionally, we will repeat a past post that continues to draw attention from readers. This post first appeared in January of 2016. The images are new. AN INTERESTING ARTICLE in the Economist points out why reading the book can sometimes be more interesting, and certainly more informative, than seeing the movie. Check out Nathaniel Philbrick's In the Heart of the Sea (Harper Collins) to read the whaling story that inspired the movie of the same name but also to learn how a group of 19th century Quakers turned the island of Nantucket and Massachusetts into a 19th century whaling powerhouse. Using a creative economic model that attracted capital investment and matched incentives to results, the leading financiers of the industry in New Bedford generated returns as high as 60% a year and average industry returns of more than 14% a year for more than seven decades! As the book and movie depict, whaling was dangerous business with trips that lasted years on the ocean to fill a ship's hold with oil. And, while there were whalers from around the world, New Bedford and Nantucket became the world's leading producers. As noted in the Economist article: "New Bedford was not the only whaling port in America; nor was America the only whaling nation. Yet according to a study published in 1859, of the 900-odd active whaling ships around the world in 1850, 700 were American, and 70% of those came from New Bedford. The town’s whalers came to dominate the industry, and reap immense profits, thanks to a novel technology that remains relevant to this day. They did not invent a new type of ship, or a new means of tracking whales; instead, they developed a new business model that was extremely effective at marshaling capital and skilled workers despite the immense risks involved for both." The whaling industry, the article notes, "was one of the first to grapple with the difficulty of aligning incentives among owners, managers and employees. . . . Managers held big stakes in the business, giving them every reason to attend to the interests of the handful of outside investors. Their stakes were held through carefully constructed syndicates and rarely traded; everyone was, financially at least, on board for the entire voyage. Payment for the crew came from a cut of the profits, giving them a pressing interest in the success of the voyage as well. As a consequence, decision-making could be delegated down to the point where it really mattered, to the captain and crew in the throes of the hunt, when risk and return were palpable." Just as with venture capital investments today, investors invested in multiple ventures to diversify risk. One firm noted in the article owned 15 ships, kept between four and nine at sea at one time, lost most of them and still turned a significant profit. The investors, being Quaker, were also frugal and open to technology improvements regardless of their source. The New Bedford system had its flaws as well. A lay system to divide a portion of profits among crew members could lead to abandoned crew members and worse. And, while the whaling industry eventually depleted the worlds population of whales and became mostly obsolete with the advent of the petroleum industry, many of the business practices they employed are used today, in modified form, in high-risk, high-return industries like venture capital. Next week we will talk about Great Baby Blues or the benefits of floating. Seriously, that's the topic. All photos and text copyright Clinton Richardson.

If you like these posts, please tell your friends about the Venture Moola blog at Readjanus.com. And, feel free to share this blog. The more readers the better. Click here to subscribe to a weekly email that tells you when we issue new entries. Or, click in the column to the left to follow us on Facebook or Twitter. THIS WILL BE THE FIRST in a series of posts on fundamental questions entrepreneurs face when they raise venture capital or angel funding. The hope is that in reviewing the basics will help when you are planning your fund raise.

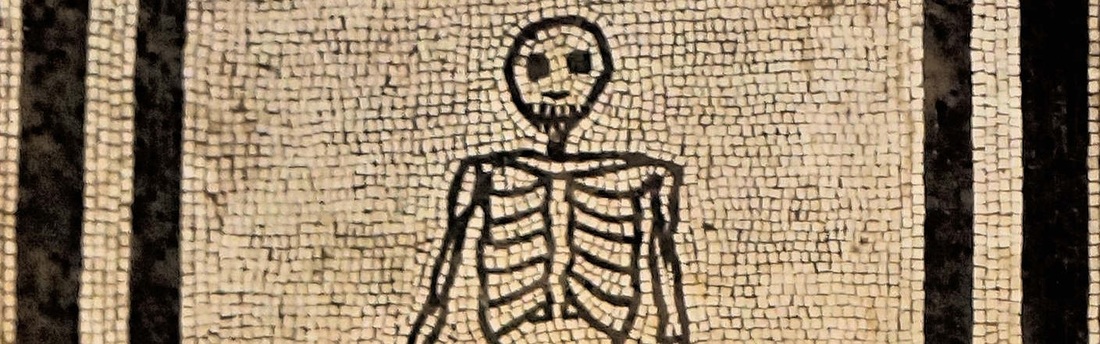

The subject came up in a conversation with an entrepreneur wanting to raise seed capital to finance the formation of three investment funds. While this is not your typical entrepreneurial endeavor and involves no high technology product, the basic questions the entrepreneur faces are the same. After working through projections about how much money the effort was going to require and nailing down costs as best he could, the entrepreneur had a big number and was getting push back from potential investors. Here are the questions I posed and what the responses were. First, did he need to raise all three funds to have a successful business? The answer was that raising the first fund would give him a viable business. Second, what would it cost to set up and raise the first fund? Here, the number dropped from millions to substantially less than one million. Third, would the effort to raise the second and third funds be substantially hampered by raising the funds sequentially instead of all at once.? The answer was no. I was trying to find the real amount the entrepreneur needed to launch his business to help him decide how much money to ask investors for. The two underlying dynamics here are that 1) investors do not like to part with money they do not have to and 2) seed investment is the most expensive money to raise. While it is nice to have a big bank of money when you are starting out, if you raise more than you need you pay a heavy price for it. Because the money is more costly, you give up more ownership than if you deferred raising some of the money until later, when you have some success and can sell your company's equity at a more favorable price. If a viable approach here is to raise money for the first fund only, start the fund and then raise money for the second and third funds later when the business can show some success, management (the entrepreneur) is likely to be left owning more of the economic value of his venture. The risk, of this approach is that the money will be hard to find later because of lack of success or reasons beyond the entrepreneur's control. And, of course, you have to spend more time looking for money. In this case, raising a smaller amount to jump start the first fund also answered the questions the entrepreneur was already fielding from the family offices he had targeted.. And, it also brought his amount down to an amount that would be easier to fund from family offices and angel investors, his primary investor focus for the fund raise. The image above is part of a mosaic found in Pompeii. Happy Halloween to all. SOMETIMES I WONDER HOW ODD a technology startup would look to the average Joe. If you described one to them, would they even believe it was a real company with strong prospects?

Here’s just one example of an early stage company with an innovative product in a highly regulated industry. It is smartly conceived, smartly executed and intelligently financed. The company, which will go unnamed here, is headquartered in the southeastern United States. Like many startups, the company started out as an idea conceived by the founder. Organized as a single member limited liability company to start, the initial funding came from friends and family in the form of notes that convert in the future, at a reasonable discount, into company ownership later when a third party financing is completed. The first work was to see if the concept for the product could be designed and built. Rather than build out a staff of employees and rent space to build the prototype, the entrepreneur hired out most of the work carefully contracting to preserve his company’s rights. As you would expect, there were some zigs and zags as the concept was fleshed out and researched with at least two significant conceptual changes to make the product what it is now. Stretching his dollars when he could by associating with a fully equipped venture incubator / accelerator and hiring out regulatory work to experts, the founder was able to compete the prototype and the product testing required to get his product ready for regulatory review. A second round of financing to get the product through regulatory review and into early commercialization became necessary after the initial financing got the company through its product design and testing. After a broad search for regional and northeastern angel investors, the best money available was from a successful serial entrepreneur with family ties to the founder. Again, a convertible note was employed with a reasonable discount to the valuation obtained when the company does its first third party financing. The need for that is anticipated next year after regulatory approval is obtained and the company gears up to commercialize the product. Of course, lots of other things have been happening with the company. Reviews of the pending product with potential users and industry thought leaders has generated strong interest. A couple of key hires have been made and the company switched its legal representation on the recommendation of one of its investors. Here’s the company today in a nutshell. It has completed its product design and testing and is beginning the regulatory approval process. Initial interest from industry thought leaders and buyers is strong. The company is a single member limited liability company with the founder as its only owner. It operates out of the founder’s basement with two employees who mostly work from their locations where special equipment and resources are more readily available but who meet at least weekly to plan. The employees have options to buy ownership in the future contingent on their meeting milestones. It has money in the bank sufficient to reasonably carry it to the next phase all in the form of convertible debt. The managing board consists solely of the founder who is presently building an advisory board. This board will not have voting rights or responsibilities to manage the company. To fill this board, he is attracting people with expertise that can help him with the challenges he will have with the business as it grows from a development company into a commercial enterprise. So here we have a modern startup. Its product is ready and going into regulatory review. It has one owner, significant debt in the form of convertible notes, one founder, only two employees, an office at home, three lawyers in one law firm in three states, two out-of-state investors, and four advisory board members in four states across the country. It also has important relationships with an incubator and service provider. And, of course, money in the bank to fuel its next stage. What it lacks in brick and mortar it makes up for in intellectual property and progress. And, what did the founder think when he saw this posting? His two big take away messages were to be frugal and to "make sure you have savings to live off for a LONG period before you jump out on your own." He said he severely underestimated how long fundraising would take because he did not believe people who told him it would take so long. Fortunately, he had saved multiples of what he thought he would need before he started. Image above copyright Clinton Richardson from Arches National Park. IT IS ONLY AN IDEA at this point but apparently a good one. The entrepreneur is striking out from a good paying job with an industry leading company to build a product he knows the industry needs. His wife works with a different employer and will support him through the effort providing financial stability and health insurance while he gets started. They have saved some in anticipation of this new venture.

After he provided his resignation and shared his plans, his employer offered to fund the development in-house and to let him lead the effort. When he said no, his boss offered to invest in his new company. He said he wanted to get in on the ground floor. Nothing specific – the entrepreneur has just begun sketching out his anticipated financial needs – but a firm offer to fund the start up in exchange for 50% of the company. They have the money to fund the prototype development, which they estimate will take less than six months. The entrepreneur’s first inclination is the decline the offer. He and his wife have heard ‘horror stories’ about entrepreneurs taking on a big investor early. This is a new experience for the entrepreneur and he wants to be cautious. What should he do? A year’s funding might involve up to $200,000. The second year would be much more expensive. Complicating matters is the nature of the business the prototype might generate. It could be a product licensed to industry companies to improve their operations. Or, it could be the basis of a service business where the company uses the technology to deliver end products or experiences customized to industry client needs. The investor is experienced in private investments but not with investments in companies like this one. The investor could provide contacts that would be helpful in the industry and possibly some credibility to this new venture. The difficulty of getting a valuation for the company at this stage that would satisfy the investor and the founder is an important factor. So too, for this entrepreneur, is the desire to develop a prototype before valuing his company. The idea of conceding 50% of the venture’s future value for as little as $200,000 is a non-starter for this entrepreneur. What we discussed, instead, was deferring the investor question until the prototype is complete or nearing completion. The risk, of course, is that the investor will cool to the investment during that time. Alternatively, the entrepreneur could try to negotiate a percentage ownership now with the investor but this will take time and money the entrepreneur is eager to put to work on his invention. Another alternative is to offer to take the money in a non-guaranteed promissory note that converts to equity later when there is more information, and hopefully another investor, to give some substance to a company valuation. Silicon Valley, specifically the Y Combinator in Silicon Valley, has come up with a third approach we do not see used much in the Southeast but which has proved useful for some companies I have worked with. That is the SAFE instrument (simple agreement for future equity). Basically, it is an agreement to invest now without a promissory note for the promise to convert the investment in the future for equity of the type being sold to other investors. Often, the instrument provides the investor with a discount to the future price. That was my recommendation in this case, if the entrepreneur decides he needs to include the investor now. I also provided some introductions so he could get other opinions. The devil, however, will be in the details. What size the discount should be and whether the investor wants to further complicate the instrument to the point that the exercise becomes too expensive or time consuming. Many investors, in their zeal to be protected and have all the terms their buddies have ever gotten, can overburden SAFE agreements with covenants that attempt to de-risk the investment beyond what’s rational. Time will tell here with more conversations to come. ENTREPRENEURS, LAWYERS AND DOCTORS share some common traits. Most are bright, competitive and focused. Most of them are good problem solvers. But sometimes being competitive and focused can get in the way of effective problem solving.

Consider an engagement I remember with some frustration. I was called in to represent six physicians with an active specialty practice. They and their practice were highly regarded and they, you could tell, considered themselves shrewd businessmen as well. Some time back they had backed the development of a new technology. The entrepreneur had worked directly for them but had since moved to independent facilities as his operation grew. The doctors were frustrated with their entrepreneur and felt less informed than they thought they should be. It had been a few years since they have made their monetary investment and they wanted to cash out. That was my engagement. To get the company to buy their stock now at a price they had designated. Usually that would be a challenge at the price point my clients wanted. Growing companies like this one, with little or no revenue, rarely have cash lying around in large bundles. They, like this company, are still dependent on inflows of cash from new investors to fuel their growth. So, diverting a large amount of cash away from the business to buy out some early shareholders usually depends on one of three things: large loans personally guaranteed by the founders, new money coming in at a higher valuation that is willing to buy stock from shareholders, or a significant pending transaction. Entrepreneurs are loath to give personal guarantees so the willingness to buy usually signals one of the two latter reasons. In this engagement, it turned out, the only challenge was timing. The company was willing to cash out all six of the investors at the designated price but needed time to get the funds together. At the same time, they were not eager to buy. They also encouraged the doctors to wait and not cash out now. They would not say why. But they agreed to let any doctor opt out from the sale. I passed this on to my clients who were still frustrated with the entrepreneur and suspicious of his motivations. They asked me what I would advise. Of course, I could not make the decision for them but I pointed out that the company’s ability to gather the cash needed to buy them out coupled with their recommendation that the doctors wait suggested that a transaction might be in the works. Their inability to say why they thought we should wait could be imposed by conditions to a pending merger, acquisition or public fundraising event. If this was true, waiting could get them a higher price. The fact that they had a couple of emergency board meetings while we were negotiating also suggested a transaction might be imminent. And, their willingness to accept our price without much negotiation indicated they thought the price was undervalued. I told them I would wait if I did not need the money now. What did they do? Five of them sold for their price. They remained suspicious of the entrepreneur’s motivations and discounted the possibility of a significant transaction. They accomplished the goal they had focused on - getting out at their price. The sixth held onto his shares. Six months later, the sixth doctor moved out of the practice after the company whose stock he kept merged into a public company and his shares became worth multiples of the price he did not sell at. Of course, there was risk in his decision. Events could have developed differently. But he answered the question "what's wrong here" by altering his immediate buy out goal and was amply rewarded. Despite the value of being laser focused, sometimes you have to ask yourself what’s wrong with a situation and consider an alternative path. Photo taken in Atlanta Georgia. The clerk at the Wild Birds Unlimited store noted the irony of being next to a chicken wing restaurant. “We feed them and they eat them." WHAT DO YOU DO when your client, who likes to self-lawyer, calls you and asks you what term you would change if you could only change one provision in a funding term sheet?

I will share my answer with you with one caveat. I do not think there is one best answer to the question especially the way it was posed to me. But, sometimes, you are called upon to make a call when there is no best answer. First, some background. I knew this client well and had worked with him for years. We had negotiated his way out of a prior business together and he had a fast growing company that needed cash badly. He loved to do his own lawyering and we knew each other well enough to kid about how he was just deferring my services until it was time to clean up his messes. And, he was very bright and good at negotiating. When he called with his question he had been searching for money for a while. A prominent West Coast venture firm was visiting as part of their diligence and had written him a big check he could cash as an advance against their full funding if and when he signed their term sheet. They were leaving in an hour and he wanted the advance money now. He would not let me see the term sheet, saying it was your typical series A convertible stock deal with the right to have a director and some class vetoes. “How long is it,” I asked. “Just a couple of pages,” he answered. So, back to the original question. If you cannot even read the term sheet and have to give an opinion about what one thing to negotiate – the client thought correctly that if he changed just one term they would sign it on the spot and release his advance check – what would you change? The valuation? The veto rights? The preferred preferences? The director rights? Or, some other restrictive term common to series A investments? Well I went a different direction. Remember, it needed to be a potentially impactful change that the business people on the scene would feel like they could change without risk. My answer? The attorney fee reimbursement obligation. I said cap the amount you have to reimburse their lawyers at a low number. An hour later I received a copy of his signed term sheet. It was short on details with only one written change initialed by both parties. The amount the company had to reimburse the investor’s lawyer for was reduced from $30,000 to $5,000. And then the fun began. A week later I got a call from a partner in the big Silicon Valley law firm representing the venture firm. He was annoyed by the attorney’s fee limitation and admitted he did not quite know what to do. "It’s not enough for us to staff this properly," he said, "or even to draft the documents." He asked if I would draft the documents (always an advantage) and said he will send me a copy of a recent funding they did for the same client with a company they bought controlling interest in. He asked me to use his documents as a form. I agreed. What I heard was that his form would not have the normal vetoes and board protections that restrict management freedom. You do not need those when you buy a controlling interest. I also heard that he was not going to think hard or critically about what we sent him if it did not look too different from his form. When I got his form, I talked with my client. The form was what I expected. It was much lighter on restrictions that a normal minority interest series A investment. So we agreed to an approach that would have me stick closely to the form adding in only what was specifically required by the sketchy term sheet. Once this was done we sent the agreement with a redline against his form to the lawyer in Silicon Valley. As we guessed, he gave it only a cursory review and we closed quickly. The client wound up with great terms in his series A that continued to flow through four more rounds of funding. On more than one occasion new investors, who felt constrained by the terms of the first round which are usually the most restrictive, noted to me that they could not believe the terms we got for the company. And the ultimate end? The prominent West Coast venture fund that provided the series A funding got it right notwithstanding the light protections in their series A stock. The entrepreneur delivered a gigantic exit after several years that provided the venture fund with its highest return in its portfolio. Would I give the same answer again? I do not know. It would depend on the circumstances. FOR COMPANIES THAT NEED TO RAISE FUNDS, it can be tempting hire legal counsel based on the lawyer’s ability to make introductions to funding sources. Not many CEO have the time to stay connected to those sources and the connections of their legal counsel can be viewed as a plus.

That’s all fine as long as the lawyers skills as a lawyer are vetted and the counsel engaged is savvy and experienced in the matters they are likely to be needed for, including venture funding documentation. And, while it may not be easy to fully vet the qualities of savvy or good judgment, you can inquire about past experience and reputation. Confident lawyers will be happy to share names of CEO’s and others they work with who can provide firsthand information about what it is like to work with them. It is not enough to rely on the general reputation of a law firm a prospective lawyer works with. The careful CEO or CFO will get granular when investigating a legal hire. Here is why it matters. Good lawyers with the right experience can save you from future headaches while helping you complete transactions on favorable terms. Consider the following example involving something as mundane and detailed as notifying shareholders about their first refusal rights while completing a Series B financing. In our example, the prior Series A financing granted rights of first refusal to investors that entitles them to purchase a pro rata share of the Series B offering. On the verge of closing a large Series B financing, the company sent out notices to the Series A shareholders telling them about the pending fund raise and giving them a fixed period to exercise their rights using a form they provided. The notice requests the Series A shareholders to either waive the first refusal right or purchase a full pro rata share. It also requests they either waive or elect to participate in buying a maximum share of first refusal shares not purchased by other Series A holders. Simple enough and, superficially at least, all appears in order. But there are details unattended to and risks being taken by the company in following an all or none approach. The risks stem from the agreements used in the Series A financing and from the fact that shares are being offered for sale. The investor rights agreement from the Series A financing grants a right to buy a pro rata share without explicitly saying whether the holder has to purchase all of the shares available or has the right to buy fewer shares. The term sheet, which preceded the investor rights agreements, and was disclosed to investors is clear that an investor can buy part or all of a pro rata share. Also, by way of background, options like this are usually interpreted absent express language to the contrary - to entitle a holder to buy less than all of the shares subject to the option. The company and its lawyer, however, have chosen to interpret the agreement to grant rights to purchase all bu not less than all of the first refusal shares. Their notice and exercise form are so constructed putting the effectiveness of the notice at risk. In addition, the first refusal agreement is unequivocal that the notice about exercising rights to buy first refusal shares not acquired by others must come later, after the company can determine how many shares are available. Failing to meet this requirement also puts the effectiveness of the company’s notice at risk. Lawyer gobbledygook, right? What possible difference could any of this make? Technical deficiencies in the notice cannot make that much difference, can they? Yes, the can. The problem is that if the notice is ineffective it can have expensive ramifications down the line for the company and other shareholders. For example, if the company goes public in the next few years, lawyers for the underwriter will diligence the Series A documents and the notice. And they will care about whether the notice was effective. If it was not valid, the first refusal rights may still be effective which means they will need to be cleaned up or disclosed as part of the offering. This can create an expensive and time consuming headache for the company just when it is eager to finance. A different, but equally annoying, set of problems can arise if the company wants to accept an offer of purchase later on. The buyer’s lawyer will do the same diligence and surface the same problem. In this context, the problem calls into question how many shares and rights to buy shares exist in the company being bought. The company will say the first refusal rights have expired. One or more Series A holders may say they still exist because the notice was defective, especially if the new share valuation is attractive. There are ways to resolve the issue but they can be expensive and time consuming to execute. So, what would you want your lawyer to do under the circumstances? Issue the notice in the form it was or fix the timing issue and describe the purchase rights consistent with the clearer language in the term sheet to avoid creating issues in the future? Most deal lawyers would not find this a difficult question to answer. But at the same time, most CEOs would not even be aware there is an issue without guidance from their lawyer on what probably feels like a minor detail. Hence the admonition about hiring attorneys. The lawyer in this instance was hired in part because he had investor connections and he comes from a big firm. He may even be good at a lot of things but the this detail of a large funding is a mess, potentially a very expensive self inflicted mess. Remember when hiring counsel: A good lawyer's primary value is in representing his or her client well with attention to details and a sensitivity to issues small and large that can impact the client. Connections can be a plus but they are dangerously not enough. Look for more on lawyers in a later posts and check out our March 14 posting about the conflicts connected lawyers sometimes bring to their entrepreneurial clients. For more about fundraising and deal terms check out Richardson’s Growth Company Guide 5.0 – Investors, Deal Structures, Legal Strategies. UNICORNS ARE STARTUP COMPANIES that have yet to perform (generate revenues) to their assumed potential but already carry valuations in excess of $1.0 billion dollars. The designation came about when the Unicorns were rare as a way to acknowledge (and romanticize) their unique status.

Unicorns are no longer rare. In 2015, it was estimated that there were 80 startups with $1.0 billion valuations. In January of this year, the estimate had climbed to 229. Combined, these 229 companies had raised $175 billion in funding and had an aggregate paper valuation of $1.3 trillion. Twenty-one of these had startup valuations of $10 billion or more. If you are struggling to raise venture capital for your company, Unicorns can point you to why you may be having problems. They are a result of what industry players refer to as the barbell. Simply put, the image of a barbell with its two weighted ends and thin bar of the barbell reflects the reality of fundraising by venture capital firms in the last decade. The money flowing into venture funds is going disproportionately into fewer, larger funds that make later stage investments and investors in early stage investments. Much of the latter group consist of individual angel investors. The bar in the middle is where money is not freely flowing – into funds that bridge the gap between startups and later stage investors. The Unicorn investors come from the big funds fueled by this barbell investing craze that sees limited partner investors (the institutions that invest in venture funds) investing in ‘big brand name’ funds. These big funds, when they do invest in early stage companies, have to put big amounts of money into play to justify their involvement. Which means they look for industry shattering ideas. When their portfolio companies spend their first money, they reinvest at higher valuations, sometimes with new investor partners. Before you know it, big idea companies with little or no revenue, by virtue of their multiple repriced rounds, have billion-dollar paper valuations. If you read my last posting, you may remember the serial entrepreneur and venture investor who is leading his newest company and his company about how difficult he was finding the current venture investment market. He is a proven commodity with a promising business and he is having trouble raising expansion capital. You may be having issues as well in a fundraising market you thought you understood. Unicorns aren’t the cause but they are a reflection of how the venture industry has changed. Their rise tells us that the venture industry we thought we knew has changed. Maybe your fundraising approach should as well. LARRY GERDES, CEO AND EXECUTIVE CHAIRMAN OF PURSUANT HEALTH, spoke at this month’s meeting of the Southern Capital Forum about his experience as a business builder and venture investor. In an engaging presentation, Larry spoke without slides or a formal presentation. Instead, he shared stories about his long career in business and investing.

Larry has been building businesses in the health care industry for more than 35 years, beginning his career as the 24 year-old banking officer in Peoria, Illinois who convinced his bosses to lend the startup company HBO & Company it’s first $1.0 million. After two more investments, Larry became CFO of HBO & Company which moved to Atlanta in 1979 and went public two years later. Larry spoke about this and the addition of Silicon Valley pioneer Don Lucas (National Semiconductor, Oracle, etc.) to the HBO board. He went on later to invest with Don Lucas and Walter Huff, founder of HBO & Company in a number of early stage companies, including several health care related investments. One of those was a predecessor to Transcend Services, Inc., where he served as Chairman and Chief Executive Officer until Transcend was acquired by Nuance Communications, Inc. Among the stories he shared was one involving Sandhill Capital, a small venture fund turned syndicate Walter Huff started with Don Lucas. Larry became a co-general partner with Don Lucas a few years later. Don Lucas got curious about a small company in their Silicon Valley office building that was working late into the night. He introduced himself to the founder, Larry Ellison, and advanced a couple of payrolls before they invested in what became Oracle. He also discussed how they switched Sandhill Capital from the traditional venture fund limited partnership model after their first fund to adopt a syndicating model with their fund investors. Each fund investor was offered the opportunity to invest in companies they sourced up to their percentage ownership in the earlier fund. If they passed on a deal, their access to future deals ended. He noted that the model served them well. Pursuant Health is an Atlanta based company where Larry currently serves as CEO. It provides health data to the managed care and provider communities to help manage large healthcare populations and is, he says, finding it challenging to raise money. He characterized the current market for early stage company fundraising as one of the most difficult he has encountered in his long career. As an experienced venture investor himself, he wondered if modern venture investors are not so focused on business models that they are under appreciating the value of good management teams. The luncheon where Larry spoke was part of the Southern Capital Forum's regular meeting schedule. The organization, founded in 1984, serves both the venture and the private equity community in the Southeast and hosts the annual Southern Capital Forum each fall that brings fund managers and their limited partner investors together to discuss the business of investing and raising capital. Today’s audience consisted predominantly of regional venture and private equity fund managers. Image copyright Clinton Richardson 2016. Detail from the Arch of Constantine in Rome. I SPENT MORE THAN 40 YEARS in the trenches advising growing businesses and their investors as a lawyer but also making angel investments and serving on a few company boards. I also served in senior management of a couple of law firms, including one with more than 1,000 professionals and offices across the country. During the same period, I co-founded what is now the oldest and largest trade association for venture capital and private equity investment firms in the Southeast and wrote a few books on deal making and legal strategies for business operators.

Hopefully, I have learned a few things that are not in the law books. Things about how the law and business can intersect effectively and creatively to the business operator's advantage. Things about how investors think and deals are negotiated. I hope the perspective I have gained and our interaction can help you avoid common entrepreneurial pitfalls and make me a more effective counselor. And, I hope we can have a lively discussion where we learn from one another. For instance, when does it make sense to consider venture capital as a financing alternative? And, when you seek venture capital, how do you go about it effectively? How should you deal with angel investors, particularly when they are family? If you are just starting, what kind of business form should you adopt? And, how should you allocate ownership among the founders? There are hundreds of these questions and few absolute answers that apply to every situation. So let's start with founder ownership for an emerging growth company, which for us will mean a company established with ambitious growth expectations that will likely need invested capital to sustain its growth. Let's say you have two founders, each with an important role in getting the company started and building its foundation for long term growth. Each is prepared to invest a similar amount to get things started. The right thing to do is give them equal shareholdings and seats on your board. Right? If you answered yes, you may be making your first big and potentially costly mistake. Between yourselves, you probably know who the driver of the new business is, the one who came up with the idea and has a real passion to make it succeed. You probably know who will be working the longer hours to get the business started and who is and will be otherwise contributing more in other ways. Try to recognize the opportunity driver from these factors and make sure the driver gets more of the stock and more rights on the board. First, it will assure you of having a person who can make decisions if there is a disagreement. Deadlock preserves the status quo which can be deadly in a new business that needs to innovate and respond quickly to survive. Second, it will force you to declare a leader and flesh out whether there are issues about who should lead and who should follow in the business. And, while you are at it, make sure you have a shareholders agreement and that ownership rights vest over time so that if a partner does not fulfill his or her anticipated future contribution, or worse, leaves the company, you can get back ownership from the non-contributing partner. Outside investors will expect management vesting of stock, so you might as well put it in place on your terms. Image (c) 2006. Galapagos scene. |

the blog

Travel, history, and business with original photos.

your hostClinton Richardson - author, photographer, business advisor, traveler. Categories

All

Archives

July 2023

Follow us on Facebook

|

Check out Ancient Selfies a 2017 International Book Awards Finalist in History and 2018 eLit Awards Gold Medal Winner and

Passports in his Underpants - A Planet Friendly Photo Safari a 2020 Readers' Favorite Winner in Nonfiction

Site Copyright 2024 by Clinton Richardson

RSS Feed

RSS Feed