|

INNOVATE, RAISE MONEY, EXPAND AND FLIP. The mantra of many modern entrepreneur. It's the classic venture capital method and dream that draws the best and the brightest to entrepreneurship. It's how many have built wealth through creativity, hard work and the leverage of OPM - other people's money.

But, what about the rest of the business world? How, for example, do you sustain a business for generations, innovating to stave off inevitable challenges and motivating family and in-laws to approach a centuries old business with entrepreneurial fervor? And, are there lessons to be learned by the entrepreneur from these successful and ageless success stories. Here are some interesting ideas from our recommended reading segment, a recent article in the Wall Street Journal entitled How to Keep a Family Business Alive for Generations. Check it out. A RECENTLY OVERHEARD discussion between a six year old and his mom:

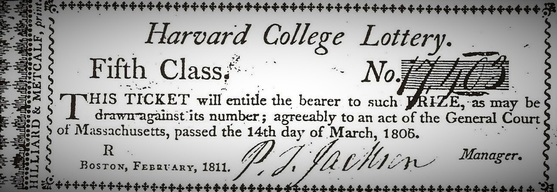

Mom: Son, we are going to buy a lottery ticket. Boy: Why would we do that? Mom: Well, if we win we will get lots of money. Boy: But, we already have money. Mom: We could buy new cars! Boy: We already have cars. Mom: We could buy a beach house. Boy: We already go to the beach. Mom: We could buy a house in the mountains. Boy: We already have a house. How could we live in three houses? This should go on the boy's resume later when he starts his own business and has to raise capital for expansion. This is someone who will look to his company's real needs when projecting how much money he needs to raise. He won't want to sell more stock than he needs to by inflating the amount he raises to include non-essential purchases. Granted, there is art involved in determining how much money a growing company needs to raise. There are variables and the future is never easy to predict. And, there is some truth in the adage that you should raise as much as you can because markets and appetites for venture investing change. But there is also evidence from earlier venture successes that staging fund raises to defer some investment until the more mature company can demand higher valuations can reduce the amount of equity a company sells to grow its business. Equity not sold is ownership retained by founders and management. The underlying attitude displayed by the boy in the conversation above is a good place to start. Image courtesy of Wikipedia, GNU Free Documentation License. AN INTERESTING ARTICLE in the Economist points out why reading the book can sometimes be more interesting, and certainly more informative, than seeing the movie. Check out Nathaniel Philbrick's In the Heart of the Sea (Harper Collins) to read the whaling story that inspired the movie of the same name but also to learn how a group of 19th century Quakers turned the island of Nantucket and Massachusetts into a 19th century whaling powerhouse.

Using a creative economic model that attracted capital investment and matched incentives to results, the leading financiers of the industry in New Bedford generated returns as high as 60% a year and average industry returns of more than 14% a year for more than seven decades! As the book and movie depict, whaling was dangerous business with trips that lasted years on the ocean to fill a ship's hold with oil. And, while there were whalers from around the world, New Bedford and Nantucket became the world's leading producers. As noted in the Economist article: "New Bedford was not the only whaling port in America; nor was America the only whaling nation. Yet according to a study published in 1859, of the 900-odd active whaling ships around the world in 1850, 700 were American, and 70% of those came from New Bedford. The town’s whalers came to dominate the industry, and reap immense profits, thanks to a novel technology that remains relevant to this day. They did not invent a new type of ship, or a new means of tracking whales; instead, they developed a new business model that was extremely effective at marshaling capital and skilled workers despite the immense risks involved for both." The whaling industry, the article notes, "was one of the first to grapple with the difficulty of aligning incentives among owners, managers and employees. . . . Managers held big stakes in the business, giving them every reason to attend to the interests of the handful of outside investors. Their stakes were held through carefully constructed syndicates and rarely traded; everyone was, financially at least, on board for the entire voyage. Payment for the crew came from a cut of the profits, giving them a pressing interest in the success of the voyage as well. As a consequence, decision-making could be delegated down to the point where it really mattered, to the captain and crew in the throes of the hunt, when risk and return were palpable." Just as with venture capital investments today, investors invested in multiple ventures to diversify risk. One firm noted in the article owned 15 ships, kept between four and nine at sea at one time, lost most of them and still turned a significant profit. The investors, being Quaker, were also frugal and open to technology improvements regardless of their source. The New Bedford system had its flaws as well. A lay system to divide a portion of profits among crew members could lead to abandoned crew members and worse. And, while the whaling industry eventually depleted the worlds population of whales and became mostly obsolete with the advent of the petroleum industry, many of the business practices they employed are used today, in modified form, in high-risk, high-return industries like venture capital.. Check out the article Before There Were Tech Startups, There Was Whaling in The Economist, January 2, 2016 - http://www.economist.com/news/finance-and-economics/21684805-there-were-tech-startups-there-was-whaling-fin-tech. Image Copyright 2008 by Clinton Richardson. FOR MORE THAN 40 YEARS, I helped entrepreneurs navigate the challenge of growing businesses and raising capital without losing control to outside investors. Having grown up in the home of an entrepreneur, it was natural that my law practice would focus on helping people who make things happen.

Over my career, I advised entrepreneurs and venture investors in Georgia, Florida, Maryland, New York, Texas, California, the European Union and elsewhere. I also wrote a book - The Venture Magazine Complete Guide to Venture Capital - that morphed into an acclaimed series of Growth Company Guides that are now in their 5th edition. And, to promote venture investment in my home of Atlanta, Georgia, I co-founded what is now the oldest and largest trade association of venture and private equity investors in the Southeast. As an attorney, I help entrepreneurs make informed choices about how they formed their companies, used equity to attract and motivate talent, and commercialized their intellectual property. I also help them plan capital raises, structure deals with venture investors and exit their mature businesses. During that same time, I also made some angel investments, sat on venture-backed boards and served in senior management of two major law firms. As an attorney, I also formed and closed investments for venture capital firms. On January 1 of 2016, I retired from big-law but not from my interest in enterprise and the Atlanta entrepreneurial community. Think of me when you are building or investing in something exciting. Maybe my experience can help you navigate the rough and tumble challenges ahead and meet your business objectives. |

the blog

Travel, history, and business with original photos.

your hostClinton Richardson - author, photographer, business advisor, traveler. Categories

All

Archives

July 2023

Follow us on Facebook

|

Check out Ancient Selfies a 2017 International Book Awards Finalist in History and 2018 eLit Awards Gold Medal Winner and

Passports in his Underpants - A Planet Friendly Photo Safari a 2020 Readers' Favorite Winner in Nonfiction

Site Copyright 2024 by Clinton Richardson

RSS Feed

RSS Feed